011—Materialists

The math of a 'good' match doesn't always add up when it comes to love (or movies)

I went into a first watch of Days of Thunder earlier this week assuming that it’d be what I’d write about today. It’s the type of earnest, action-oriented early ‘90s movie I find fun, is directed by Tony Scott (same director as the beloved film Top Gun), and it stars Mr. Movie himself, Tom Cruise. By plugging in racecars for fighter jets, Days of Thunder followed a previously successful formula, but instead of movie magic the result was a dull, hollow dupe. Basically, it checked a lot of my movie boxes, yet the experience I had watching it fell short.

The last time I remember having a ‘good on paper’ movie encounter was funnily enough with Celine Song’s acclaimed debut, Past Lives (this review by Chicago critic Angelica Jade Bastien mostly captures my sentiments). When I saw that Song had directed and written the Materialists, I was interested in giving a film of hers another go. I went in expecting a messy love triangle, but was gobsmacked to find the crux of the plot hinging on a 35ish-year-old-woman’s belief that a good match is simply good math, namely a partner that checks all of the must have boxes and none of the non-negotiables.

Lucy (Dakota Johnson) is a pragmatist who’s successful in her career as a matchmaker. With nine client marriages under her belt, she’s good at ‘doing the math’ (a phrase Song over indexes on throughout the movie) and pairing her single clients together the way a skilled strategist would. While she treats her clients with compassion and a lack of judgment, Lucy talks about them as if they’re merchandise that needs to be marketed appropriately with a coworker.

She tells her clients they’ll marry the love of their lives, but it’s not clear that Lucy believes in romance or at least she doesn’t think love is enough. To her, marriage is a business deal between two people both investing in something whether that be a late-life caretaker, a desire to feel valued, or financial security. She’s a materialist, who is striving to leave childhood poverty behind through upward social mobility of her own means or by marriage to an incredibly rich man. Her dedication to her beliefs and approach to life are portrayed in a flashback scene where we learn that she broke up with her long-term partner John (Chris Evans) due to financial incompatibilities. He was poor, and even though she was self-aware enough to hate herself for caring about something as material as money, the fact remained that she did.

Lucy tells her clients dating is a requires risk, and yet the check lists, ‘the math’, seem antithetical to that risk in that they’re built to bypass any vulnerabilities or friction in dating in order to guarantee compatibility and a good match. A desire for certainty shuts out mystery, and inexplicabilities of desire. There’s no room for the soft animal of the body to love what it loves.

This plays out for Lucy, when she meets Harry Castillo (Pedro Pascal) at the wedding reception of a client. He’s hot, respectful, charismatic, interested in Lucy, and obscenely rich. Harry is a unicorn, but instead of jumping for joy Lucy is skeptical at first. The math isn’t fully checking out, and while she’s aware of a dissonance, she’s not forced to reckon with her own previously uninterrogated belief system until a client of hers experiences a traumatic event.

What follows is an unraveling and then a revelation about relationships and love. This is also where the movie started to fall apart for me in terms of narrative decisions driven by plot versus logic (Lucy seemingly has no friends and no therapist) at the expense of the character that had been established for the first two-thirds of the movie.

Instead of pairing her pragmatism with her newfound romanticism, Lucy leaps into a ‘bad financial decision’ going all in on a romantic match that is seemingly as incompatible as it always was. Instead of Lucy welcoming love and romance into her life, while still honoring herself or getting creative about how to work with her non-negotiables by say, becoming her own rich man, we see her contemplate leaving her job which just offered her a ‘name any salary’ promotion as if money, or material realities no longer exist at all.

And instead of concluding with a modern, nuanced take on romance, Song chose to reinforce outdated ideas about romantics/romance as fantasy-prone, foolish, and impractical. I was expecting something more complex ala the ending of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag, but was left with the reductive materialism=bad and romance=good.

That all said…despite it’s narrative flaws and missteps, despite it not checking all of my boxes and existing foundationally as a two star movie, I found myself liking it and giving it four stars, in my heart. What can I say? Desire isn’t always sensible.

Movies this is in conversation with

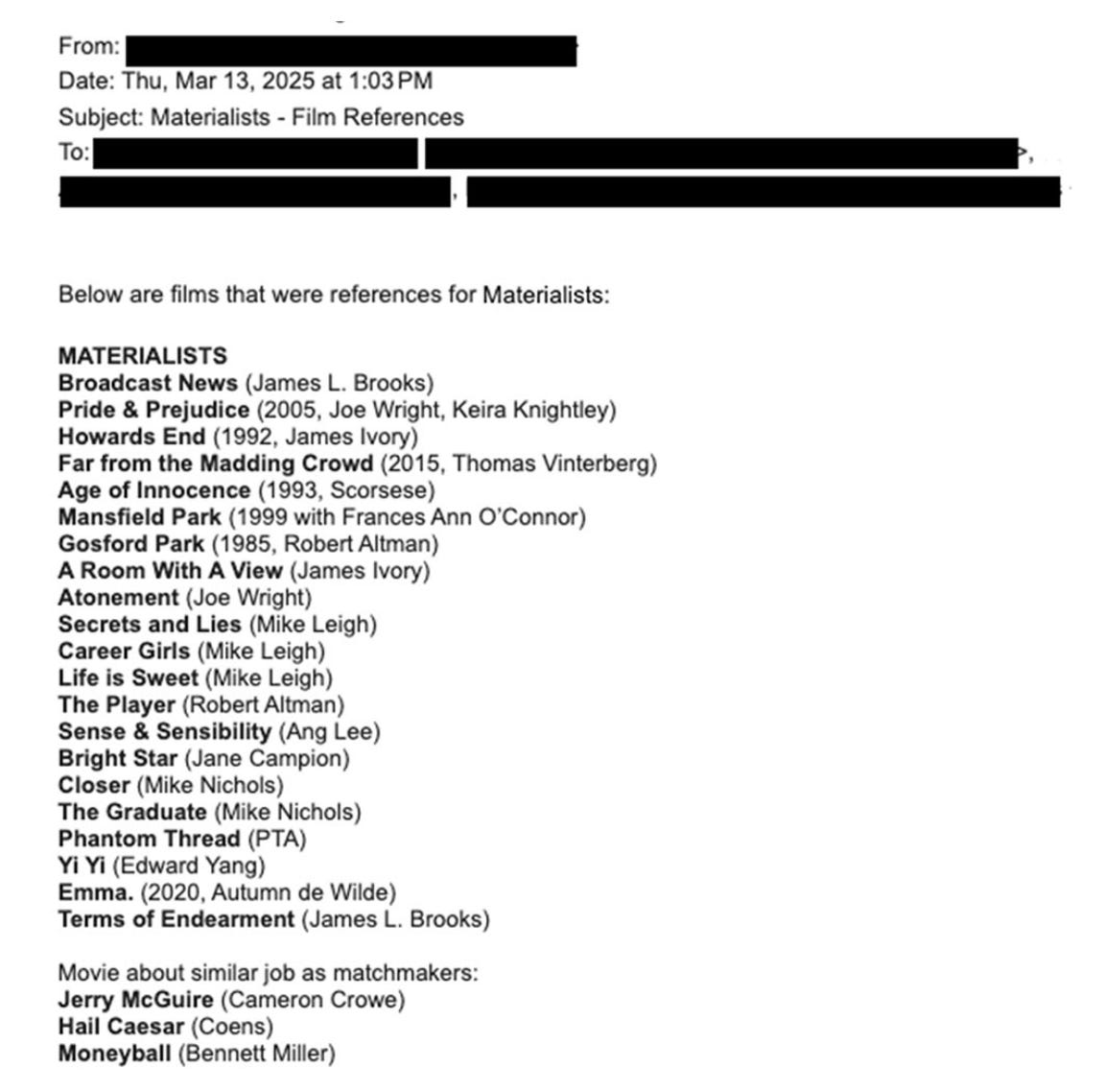

A24 put out this ‘syllabus’/list of references that Celine drew from. A few others that came to mind to me were:

Other movies watched this week

Mansfield Park, Far from the Madding Crowd, Days of Thunder, Don’t Be Long, Little Bird, Naz & Maalik, 28 Weeks Later, 28 Days Later, Being John Malkovich, Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person, and A Still Small Voice.